If you’ve ever been to a dog park, you’ve likely come across the great pyrenees: a massive canine with the look of a dandelion puffball and the courage of an elephant. But have you ever met the Greatest Piranese? That honor is reserved for Giuseppe Tartini, a composer born in the small town of Piran (which was situated on the peninsula of Istria, and which is now a part of Slovenia).

In Tartini’s childhood, his native Piran was a part of the Republic of Venice, the local governor being an appointed man from Florence (Gianantonio Zangrando) and his wife Caterina (who was a descendant of one of the oldest aristocratic families in Piran). Tartini’s parents were set on him becoming a Fransiscan friar, and so they took the appropriate measures to ensure he was musically trained. But it soon became clear that Tartini was not destined for monastic greatness, as he had his eye set on law. Leaving Piran, he journeyed to the University of Padua, where he began to study law and hone his fencing skills.

The death of his father in 1710 prompted him to settle down, but he defied his parents’ expectations of him once more: he married Elisabetta Premazore, a woman his father would never have given him blessing to wed. Elizabetta’s lower social class and age difference to Tartini didn’t bother the latter one bit, and it seemed as though a happy ending were in store for the two newly-weds. That is, until the intervention of the powerful Cardinal Giorgio Cornaro!

Elizabetta was the apple of Cardinal Cornaro’s eye, and he promptly charged Tartini with abduction. Fleeing Padua and a distraught Elizabetta, Tartini took refuge in the monastery of St. Francis in Assisi in order to escape prosecution. It was almost as if his parents had been trying to help him avoid this traumatic turn of events all along. During his stay with the Fransiscan friars, Tartini began practicing the violin as a hobby.

But Tartini was competitive by nature, and when he heard Francesco Maria Veracini’s playing in 1716 (and realized he had a long way to go before reaching violin mastery), he fled the friars to find lodgings in Ancona. According to music historian Charles Burney, Tartini would lock himself inside his chambers for hours every day with his violin “in order to study the use of the bow in more tranquility, and with more convenience than at Venice.”

Tartini’s violin playing improved greatly over the next five years, so much so that he was appointed Maestro di Cappella at the Basilica di Sant’Antonio in Padua, the very same Padua he had fled at the “encouragement” of Cardinal Cornaro. His contract there allowed him to play for other institutions if he wished, and while in Padua he befriended fellow composer and theorist Francesco Antonio Vallotti. By now the Cardinal had all but forgotten about Tartini, and he was able to reinvent his life in Padua with a new friend by his side.

Tartini was the first known owner of a violin made by the famed instrument builder Antonio Stradivari. The violin itself was his pride and joy, fashioned in 1715 and passed down to Tartini’s student Salvini, who in turn gave it to Polish composer and virtuoso violinist Karol Lipiński upon hearing him perform. One of the most famous violins in the world, the instrument is known today as the Lipinski Stradivarius. Tartini was also fortunate enough to own and play another Stradivarius violin (the ex-Vogelweith) which had been fashioned in 1711.

Five years into his position in Padua, Tartini started a violin school which attracted students from across Europe. As he grew more proficient on the violin he became more fascinated in the theory of harmony and acoustics, and published treatises on this subject from 1750 to the end of his life. Giuseppe Tartini laid down his bow for the last time surrounded by friends and students in Padua. A statue of Tartini was erected in the square of the composer’s home town of Piran to commemorate him and all he contributed to the world of music during his lifetime. Not only that, they named the entire square and even a hotel after him! His birthday is celebrated by a concert in the main town cathedral to this very day.

While the vast majority of Tartini’s compositional output are violin concerti and sonatas, he did pen a few sacred works (such as Miserere, composed between 1739 and 1741 at the request of Pope Clement XII). Tartini’s music poses increasing problems for scholars and editors interested in sharing his music with the world, because the composer never dated his manuscripts. He also had the infuriating habit of revising his finished works, meaning that placing his compositions on a timeline is nearly impossible to do. The greatest effort made towards solving this problem was undertaken by scholars Minos Dounias and Paul Brainard (who have attempted to divide Tartini’s works into stylistic periods based on the musical characteristics of each individual piece.

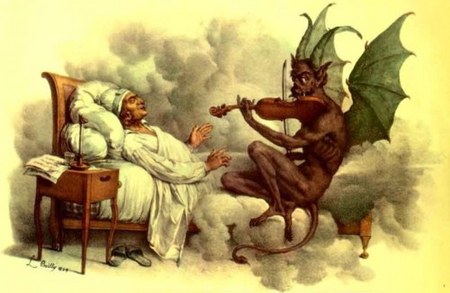

Today, musical scholars can all agree that Tartini’s most enduring work is the “Devil’s Trill Sonata”. This solo violin sonata requires a number of demanding double stop trills, difficult even by modern standards. An urban legend spread by the Russian Philosopher Madame Blavatsky claimed that Tartini was “inspired to write the sonata by a dream in which the Devil appeared at the foot of his bed playing the violin”. This hectic piece is daunting even to the most experienced violinists, and only played in public by those who are willing to risk carpal tunnel syndrome!

But Tartini’s genius was not merely reserved to his compositions for the violin. Tartini was also a music theorist, and is credited with the discovery of sum and difference tones. His treatise on ornamentation was eventually translated into French in 1771, and is still useful as the first published text devoted entirely to ornament. In modern times, this text has provided first-hand information on violin technique for historically informed performances. A later edition of this text includes a facsimile of the original Italian, copied in the hand of Giovanni Nicolai (one of Tartini’s best known students) and which features an opening section on bowing and a closing section on how to compose cadenzas not previously known.

A remarkable composer and violinist, Giuseppe Tartini will forever be remembered for his seemingly “supernatural” abilities on the violin, earned through a great deal of practice and dedication to his craft!