Harry Somers’ “Picasso Suite” was commissioned by the SSO in 1964 and received its premiere performance in Saskatoon. Since that first performance, it has gone on to be one of Canada’s most loved orchestral suites, and an audience favourite across the country!

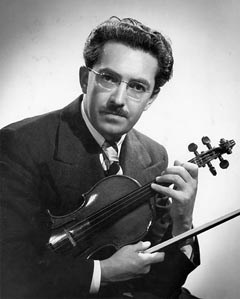

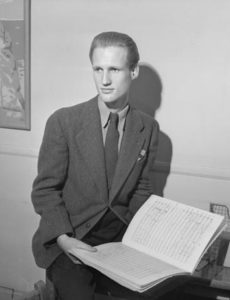

Harry Somers was one of the most influential and innovative contemporary Canadian composers of the past century. Possessing a charismatic attitude and rather dashing good-looks, as well as a genuine talent for his art, Somers earned the unofficial title of “Darling of Canadian Composition.” A truly patriotic artist, Somers was engaged in many national projects over the course his lifetime.

Each of the movements in this suite provide musical interpretations of the many artistic phases which defined the life and art of Pablo Picasso. An invigorating blast of musical color begins the suite, recalling all the sights and fragrances of Paris at the turn of the 20th century.

Picasso has struck the Parisian art scene, a meteor of brilliance brimming with raw potential, and the world of classical art will never be the same. Just as suddenly as he arrives, the Spanish-born artist’s captivating colors are musically withdrawn into themselves.

What emerges from the silence are Somers’ sonic representations of the paintings which represent Picasso’s Blue Period. Somers utilizes the oboe’s potential for melancholy to full effect in this second movement. This is a movement that plays with the listener’s other senses, and which invites them to delve into the textures belonging to these paintings: the smooth pallid skin of his “Old Guitarist”, the warmth of the steam that is central to “La Soupe”, and the stale taste of dust that lingers in the air of his “La Vie”.

Transfixed by this rich introspection, we are caught off guard as the rolling thunder of percussion ushers in a new artistic phase: The Rose Period. Titled “Circus” by Somers, this movement conjures all the delight experienced by a child under the Big Top. This musical calliope spins us through the cheerful orange and pink hues of Picasso’s Rose Period, while broad-nosed figures from his African-Influenced Period dance vibrantly into focus. Somers uses this playful romp to tremendous effect, recalling the youthful vitality of Picasso’s painted women in “Les Demoiselles D’Avignon”.

One by one they strike a pose and skip away, as the musical calliope grinds slowly to a halt and a dissonant chord contorts the face of one lingering woman. Somers then begins to interpret the most iconic phase of Picasso’s life as an artist, one which owes a considerable debt to the stylized features of traditional African masks: his Cubist Periods. As we soar through the decade spanning 1909 to 1919, clusters of bent notes rain from the sky. Out of the mist, there seeps a sense of dread which culminates in a symphonic homage to one of the most prolific depictions of atrocity ever put to canvas: the infamous black and white mural “Guernica”.

Left in silence once more, the fifth movement’s plaintiff melody explores Picasso in the years immediately following World War One. Picasso’s muse returns in a new form, voiced by a soothing oboe melody, and spurs his artistic mind onward to bathe in the clean bright light of the Neoclassical style. Excitement bubbles forth as Somers falls into a fascination with lyrical spins and flourishes, illustrating the more bizarre offerings of Picasso’s Surreal Period.

Riding on the crest of this wave, we feel Picasso grow introspective once more. Stirring in the listener a longing for the innocence of the third movement, the brass call out to echo the valor of those who lost their lives on the field of battle. A delicate voice from a music box lulls Picasso into a deep slumber, and he dreams of a project that will consume most of his waking moments for the next four years: The Vollard Suite.

Art historians believe that many of the figures depicted in the Vollard Suite’s 100 etchings were inspired by Honore de Balzac’s 1831 short story “The Unknown Masterpiece”. The story revolves around a painter who attempts to capture life itself on canvas through depictions of feminine beauty, and Somers tasks the erotic lilt of the flute alone with capturing the sensual and manic devotion of the artist rendering his muse.

As did the style of the etchings themselves, Picasso’s temperament shifted wildly over the period spanning 1933 to 1937, with the spread of fascism through Europe darkening those clouds that had been cast over the artist’s mind. The virtuosity of the sixth movement trickles away to reveal one of the final images in the series: the once virile minotaur, now blind and impotent, being led to safety by a young girl.

The seventh movement, oddly titled “Temple of Peace” may be musically comforting in its initial majesty, but a glance outside of its pristine chamber betrays the arching shapes of strange architecture peeking from an even stranger garden. Picasso is still troubled, still searching to reclaim his youthful innocence. Punctuated by an unsettling violin motif, Somers creates in this movement a sense of motion towards something important while utilizing precious little melody.

The return of the music box signals the arrival of the eighth movement, as well as an epiphany crystalizing in the mind of the aging Picasso. He abandons the cold safety of the temple for the warm rain of the lush garden. Pushing his way through ever-thickening foliage, the garden eventually gives way to jungle. Emerging into a clearing at last, Picasso meets his alter-ego: the faun. Playing his double-flute with unbridled ease, the faun guides Picasso deeper into the wild and teaches him how to find peace within himself. The melody of his Rose Period “Circus” days come back in flashes, and Picasso is finally at home with himself again after so many years.

In the final movement, Codetta, Pablo Picasso can finally revisit his first few bombastic years in Paris unencumbered. As Picasso once remarked, “It takes a long time to become young.” Unconventional and riveting to its core, Harry Somers’ “Picasso Suite” is among the finest of artistic tributes to a man whose life’s work birthed whole new possibilities of creation for artists worldwide.