Symphony No. 41 is the last of a set of three that Mozart composed in rapid succession during the summer of 1788. No. 39 was completed on 26 June and the No. 40 on 25 July.[1] Nikolaus Harnoncourt argues that Mozart composed the three symphonies as a unified work, pointing, among other things, to the fact that the Symphony No. 41, as the final work, has no introduction (unlike No. 39) but has a grand finale.[3]

Around the same time as he composed the three symphonies, Mozart was writing his piano trios in E major (K. 542), and C major (K. 548), his piano sonata No. 16 in C (K. 545) – the so-called Sonata facile – and a violin sonatina K. 547.

It is not known whether Symphony No. 41 was ever performed in the composer’s lifetime. According to Otto Erich Deutsch, around this time Mozart was preparing to hold a series of “Concerts in the Casino” in a new casino in the Spiegelgasse owned by Philipp Otto. Mozart even sent a pair of tickets for this series to his friend Michael Puchberg. But it seems impossible to determine whether the concert series was held, or was cancelled for lack of interest.[1]

Movements[edit]

The four movements are arranged in the traditional symphonic form of the Classical era:

- Allegro vivace, 4 4

- Andante cantabile, 3 4 in F major

- Menuetto: Allegretto — Trio, 3 4

- Molto allegro, 2 2

The symphony typically has a duration of about 33 minutes.

4\f r8 } ” src=”https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/9/n9mqqvlym36e19aiczzkmmokh9qmttx/n9mqqvly.png”>

The sonata form first movement’s main theme begins with contrasting motifs: a threefold tutti outburst on the fundamental tone (respectively, by an ascending motion leading in a triplet from the dominant tone underneath to the fundamental one), followed by a more lyrical response.

This exchange is heard twice and then followed by an extended series of fanfares. What follows is a transitional passage where the two contrasting motifs are expanded and developed. From there, the second theme group begins with a lyrical section in G major which ends suspended on a seventh chord and is followed by a stormy section in C minor. Following a full stop, the expositional coda begins which quotes Mozart’s insertion aria “Un bacio di mano”, K. 541 and then ends the exposition on a series of fanfares.[4] The development begins with a modulation from G major to E♭ major where the insertion-aria theme is then repeated and extensively developed. A false recapitulation then occurs where the movement’s opening theme returns, but softly and in F major. The first theme group’s final flourishes then are extensively developed against a chromatically falling bass followed by a restatement of the end of the insertion aria then leading to C major for the recapitulation.[4] With the exception of the usual key transpositions and some expansion of the minor key sections, the recapitulation proceeds in a regular fashion.[4]

The second movement, also in sonata form, is a sarabande of the French type in F major (the subdominant key of C major) similar to those found in the keyboard suites of Johann Sebastian Bach.[4]

The third movement, a Menuetto marked allegretto is similar to a Ländler, a popular Austrian folk dance form. Midway through the movement there is a chromatic progression in which sparse imitative textures are presented by the woodwinds (bars 43–51) before the full orchestra returns. In the trio section of the movement, the four-note figure that will form the main theme of the last movement appears prominently (bars 68–71), but on the seventh degree of the scale rather than the first, and in a minor key rather than a major, giving it a very different character.

Finally, a remarkable characteristic of this symphony is the five-voice fugato (representing the five major themes) at the end of the fourth movement. But there are fugal sections throughout the movement either by developing one specific theme or by combining two or more themes together, as seen in the interplay between the woodwinds. The main theme consists of four notes:

Four additional themes are heard in the “Jupiter’s” finale, which is in sonata form, and all five motifs are combined in the fugal coda.

In an article about the Jupiter Symphony, Sir George Grove wrote that “it is for the finale that Mozart has reserved all the resources of his science, and all the power, which no one seems to have possessed to the same degree with himself, of concealing that science, and making it the vehicle for music as pleasing as it is learned. Nowhere has he achieved more.” Of the piece as a whole, he wrote that “It is the greatest orchestral work of the world which preceded the French Revolution.”[5]

The four-note theme is a common plainchant motif which can be traced back at least as far as Josquin des Prez‘s Missa Pange lingua from the sixteenth century. It was very popular with Mozart. It makes a brief appearance as early as his Symphony No. 1 in 1764. Later, he used it in the Credo of an early Missa Brevis in F major, the first movement of his Symphony No. 33 and trio of the minuet of this symphony.[6]

Scholars are certain Mozart studied Michael Haydn‘s Symphony No. 28 in C major, which also has a fugato in its finale and whose coda he very closely paraphrases for his own coda. Charles Sherman speculates that Mozart also studied Michael Haydn’s Symphony No. 23 in D major because he “often requested his father Leopold to send him the latest fugue that Haydn had written.”[7] The Michael Haydn No. 39, written only a few weeks before Mozart’s, also has a fugato in the finale, the theme of which begins with two whole notes. Sherman has pointed out other similarities between the two almost perfectly contemporaneous works. The four-note motif is also the main theme of the contrapuntal finale of Michael’s elder brother Joseph’s Symphony No. 13 in D major (1764).

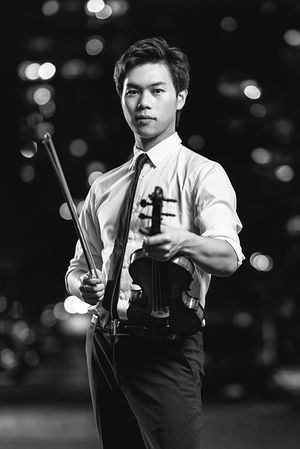

Canadian Violinist, Timothy Chooi has been described as “the miracle (Montreal Lapresse)”.

Canadian Violinist, Timothy Chooi has been described as “the miracle (Montreal Lapresse)”.