“Intensely soulful… Virtuoso” The New York Times

“Intensely soulful… Virtuoso” The New York Times

“[Azmeh’s] rhapsodic clarinet [is] able to seduce with a rare intimacy and explode in ecstasy.” Los-Angeles Times

“Spellbinding!” The New Yorker

“brilliant liquidity and meltingly beautiful tone” The Times, London

Hailed by critics and audiences alike, winner of Opus Klassik award in 2019 clarinetist and composer Kinan Azmeh has gained international recognition for his distinctive voice across diverse musical genres.

Originally from Damascus, Syria, Kinan Azmeh brings his music to all corners of the world as a soloist, composer and improviser. Notable appearances include the Opera Bastille, Paris; Tchaikovsky Grand Hall, Moscow; Carnegie Hall and the UN General Assembly, New York; the Royal Albert Hall, London; Teatro Colon, Buenos Aires; Philharmonie, Berlin; the Library of Congress, the Kennedy Center, Washington DC; the Mozarteum, Salzburg, Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie; and in his native Syria at the opening concert of the Damascus Opera House.

He has appeared as a soloist with the New York Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, Seattle Symphony, Bavarian Radio Orchestra, Dusseldorf Symphony, the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, The Azerbaijan State Symphony, Winnipeg Symphony, Symphony Nova Scotia, Toronto Symphony, A Far Cry, The Knights Orchestra, Calgary philharmonic, Qatar Philharmonic and the Syrian Symphony Orchestra among others, and has shared the stage with such musical luminaries as Yo-Yo Ma, Daniel Barenboim, Marcel Khalife, John McLaughlin, Francois Rabbath, Aynur and Jivan Gasparian.

Kinan’s compositions include several works for solo, chamber, and orchestral music, as well as music for film, live illustration, and electronics. His resent works were commissioned by The New York Philharmonic, The Seattle Symphony, The Knights Orchestra, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Elbphilharmonie, Apple Hill string quartet, Quatuor Voce, Brooklyn Rider, Cello Octet Amsterdam, Aizuri Quartet and Bob Wilson.

An advocate for new music, several concertos were dedicated to him by composers such as Kareem Roustom, Dia Succari, Dinuk Wijeratne, Zaid Jabri, Saad Haddad and Guss Janssen, in addition to a large number of chamber music works.

In addition to his own Arab-Jazz Quartet CityBand and his Hewar trio, he has also been playing with the Silkroad Ensemble since 2012, whose 2017 Grammy Award-winning album “Sing Me Home” features Kinan as a clarinetist and composer.

Kinan Azmeh is a graduate of New York’s Juilliard School as a student of Charles Neidich, and of both the Damascus High institute of Music where he studied with Shukry Sahwki, Nicolay Viovanof and Anatoly Moratof, and Damascus University’s School of Electrical Engineering. Kinan earned his doctorate degree in music from the City University of New York in 2013.

His first opera “Songs for Days to Come” which is fully sung in Arabic, was recently premiered in Osnabruck, Germany in June 2022 to a great acclaim. He has recently been appointed to the National Council for the Arts on a nomination by President Joe Biden.

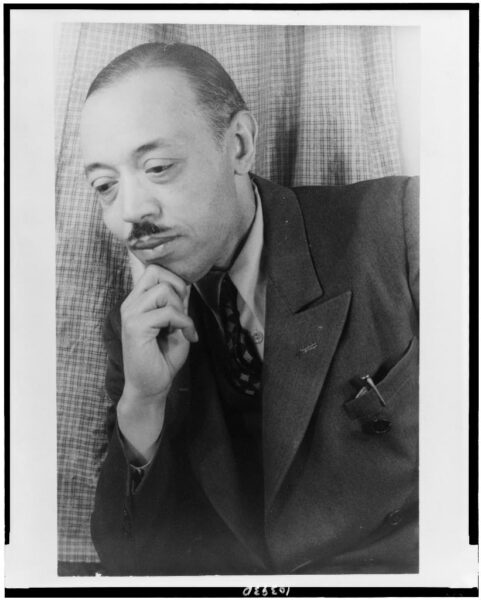

Long known as the “Dean of African-American Classical Composers,” as well as one of America’s foremost composers, William Grant Still has had the distinction of becoming a legend in his own lifetime. On May 11, 1895, he was born in Woodville (Wilkinson County) Mississippi, to parents who were teachers and musicians. They were of Negro, Indian, Spanish, Irish and Scotch bloods. When William was only a few months old, his father died and his mother took him to Little Rock, Arkansas, where she taught English in the high school. There his musical education began–with violin lessons from a private teacher, and with later inspiration from the Red Seal operatic recordings bought for him by his stepfather.

Long known as the “Dean of African-American Classical Composers,” as well as one of America’s foremost composers, William Grant Still has had the distinction of becoming a legend in his own lifetime. On May 11, 1895, he was born in Woodville (Wilkinson County) Mississippi, to parents who were teachers and musicians. They were of Negro, Indian, Spanish, Irish and Scotch bloods. When William was only a few months old, his father died and his mother took him to Little Rock, Arkansas, where she taught English in the high school. There his musical education began–with violin lessons from a private teacher, and with later inspiration from the Red Seal operatic recordings bought for him by his stepfather.

Daniel Clarke Bouchard began playing the piano at the age of five and gave his first piano recital at the age of six. He received the Grand Prize at the Joy of Music Festival held at McGill University. In 2009, he won the gold medal at the Montreal Classical Music Festival. In 2010, he won Gold at the Quebec Music Educators Association Competition. In 2011, Daniel won first place at the Canadian Music Competition and received the Yamaha, Canimex and Gilles Chatel scholarships.

Daniel Clarke Bouchard began playing the piano at the age of five and gave his first piano recital at the age of six. He received the Grand Prize at the Joy of Music Festival held at McGill University. In 2009, he won the gold medal at the Montreal Classical Music Festival. In 2010, he won Gold at the Quebec Music Educators Association Competition. In 2011, Daniel won first place at the Canadian Music Competition and received the Yamaha, Canimex and Gilles Chatel scholarships.