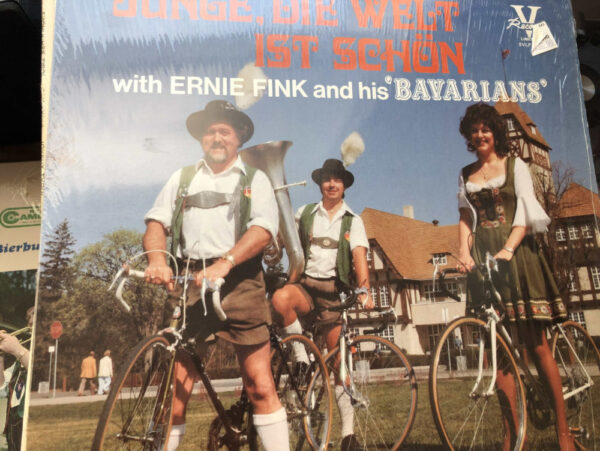

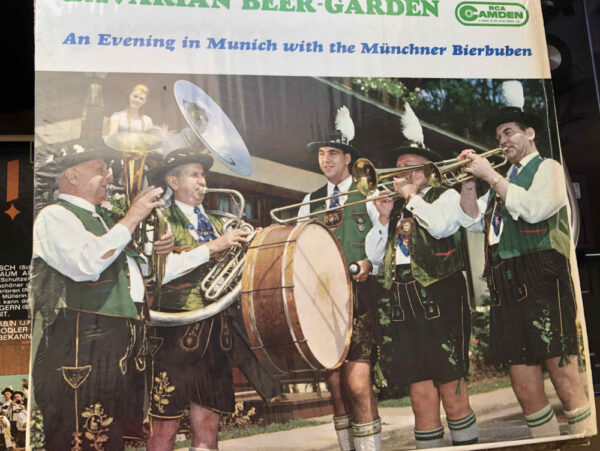

It’s one of the biggest parties in the world…and its a whole lot of fun! Oktoberfest is a celebration that happens every fall in Munich.

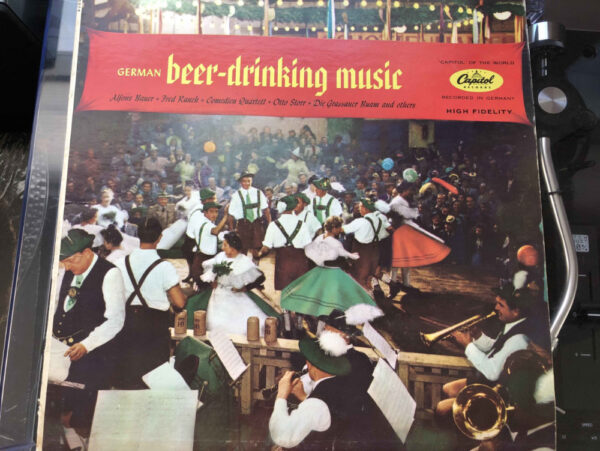

Oktoberfest is the world’s largest Volksfest (beer festival and travelling funfair). Held annually in Munich, Bavaria, Germany, it is a 16- to 18-day folk festival with more than six million people from around the world attending the event every year. Locally, it is called d’Wiesn, after the colloquial name for the fairgrounds, Theresienwiese. The Oktoberfest is an important part of Bavarian culture, having been held since the year 1810. Other cities across the world also hold Oktoberfest celebrations that are modeled after the original Munich event.

With our musical adventure programming this year, we’re encouraging everyone who’s watching from home to make a night of it – with each concert featuring a different travel destination, each watch party is a completely new experience to make your night with the SSO something really special.

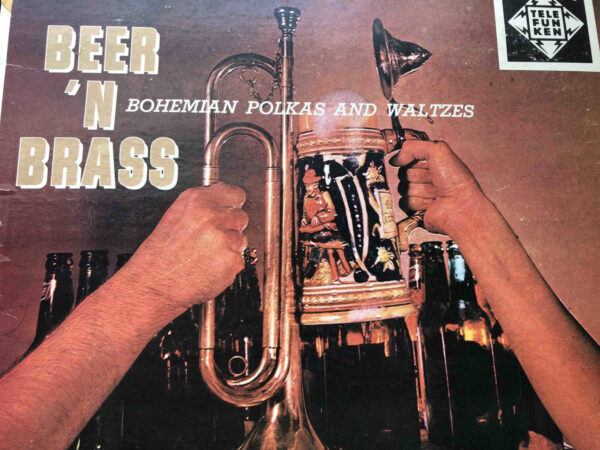

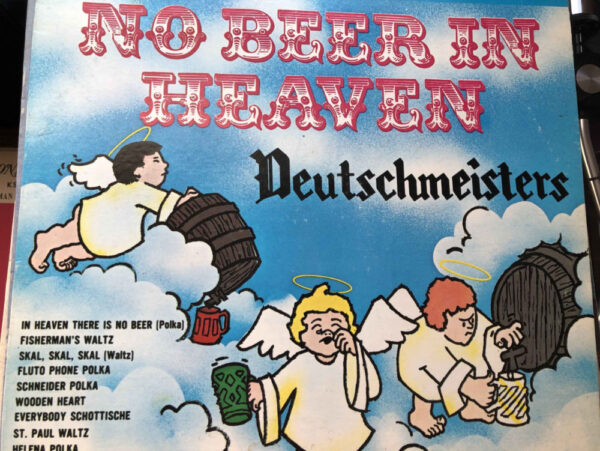

For Oktoberfest…well its all about beer!

Find out more about our Oktoberfest concert

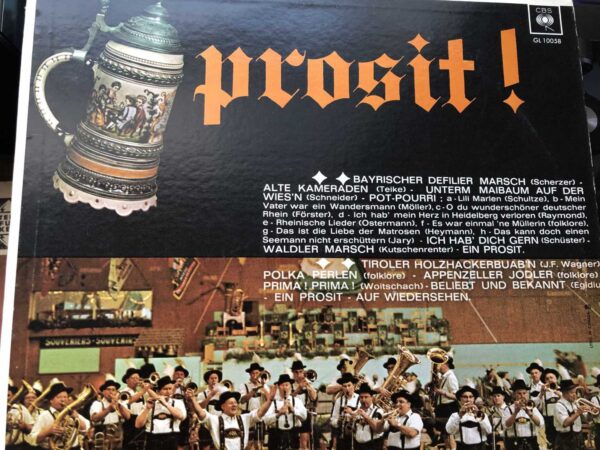

Drinks

So the real Oktoberfest, the beer has to be from one of Munich 6 breweries – Paulaner, Spaten, Hacker-Pschorr, Augustiner, Hofbräu, and Löwenbräu. Each serving tent has beer from the main brewery that sponsors that tent. Your ordering options are limited mainly to:

- Helles (Light Beer)

- Dunkel (Dark Beer)

- Radler (Shandy) (which is 50% Helles mixed with 50% Lemon Soda (Sprite)

A few tents also carry the following beer options:

- Hefeweizen (Wheat Beer)

- Russ (just like Radler but with Wheat Beer instead of Light)

For the SSO’s Oktoberfest – we’re asking you to go local with your beer. Saskatoon has an embarrassment of riches when it comes to craft beer. You name it, the Saskatoon breweries have it for you. Why not plan ahead and get some beer from a number of local brewers – then as you enjoy the concert you can “move on to the next tent” in your very own home!

Oktoberfest also presents a chance to try the wealth of other Bavarian treats, like Schnapps!

A great little sweeter alcohol to sip on, German schnapps is a syrup-like texture and a taste sensation. Common flavors include Kirsch (cherry), Apfel (apple), and of course Pfefferminz (peppermint). If you’re looking for something non-alcoholic, you can’t go wrong with Apfelschorle – a delicious apple juice, perfect for the season!

Food

So. Much. Food.

If you’ve ever been to Munich for Oktoberfest, you’ll know that its truly a feast. No wonder they dance so much, they have to work off all that food…and beer!

While you can’t have the full Oktoberfest experience, you can eat like you’re there. Here, 11 traditional Oktoberfest foods.

Roast Chicken

During Oktoberfest, chickens are spit-roasted until the skin is golden brown and crispy. Most people don’t have a rotisserie set up at home, so instead make this classic lemon-thyme roast chicken in the oven. Rubbing a lemon-and-thyme butter over the chicken before roasting ensures superbly crispy skin.

Schweinebraten (roast pork)

A classic Bavarian dish, schweinebraten can be made with a variety of pork cuts, like shoulder or even loin. It’s traditionally roasted with dark beer and onions. For a quick and easy take on the dish, try this pounded pork tenderloin smothered in onion and mustard.

Schweinshaxe (roasted ham hock)

A beloved beer hall classic, roasted ham hock or shank (pig knuckles) are crispy on the outside with tender meat. They’re surprisingly easy to make at home. Try it with Andrew Zimmern’s delicious recipe.

Steckerlfisch (grilled fish on a stick)

Simple and fairly self-explanatory, steckerlfisch is marinated, skewered and grilled fish typically made with local Bavarian fish, like bream, though it can also be made with trout or mackerel. At home, try quick-grilling sardines.

Würstl (sausages)

Würstl refers to a variety of classic Bavarian sausages. Try them at home sautéed in a skillet with bacon and apple sauerkraut. Serve with plenty of mustard.

Brezen (pretzels)

You can’t have Oktoberfest without pretzels. Large and soft, they’re the perfect accompaniment to beer. Try making your own with this über-authentic recipe for German-style pretzels.

Knödel (potato or flour dumplings)

These are large, dense, ultra-comforting dumplings, common in Central Europe. While these potato dumplings are technically Hungarian, the idea is the same. They are like rustic gnocchi.

Käsespätzle (cheese noodles)

This is a savory, cheesy version of spätzle, a traditional egg noodle. This recipe, made with small-curd cottage cheese, is topped with tangy quark, for a doubly cheesy dish.

Reiberdatschi (potato pancakes)

These potato pancakes are served both savory with a salad or sweet with apple sauce. Reiberdatschi are a lot like latkes, so follow Andrew Zimmern’s killer latke recipe for hot and crisp results.

Sauerkraut

If you’re attending Oktoberfest, you’re eating this pickled cabbage with almost anything. This homemade version mixes cabbage with sweet apples and aromatic caraway.

Obatzda (spiced cheese-butter spread)

This might be your new favorite spread. It’s aged soft cheese, like Camembert, mixed with butter, a small amount of beer, and spices including paprika, salt, pepper and garlic. Try this upscale version, made with crème fraîche and Dijon mustard along with farmer’s cheese and, of course, butter.

If you’re looking to order in for your watch party at home, the Granary has you covered. They have a phenomenal Oktoberfest menu for this whole month – give them a call at 306-373-6655

Find out more about our Oktoberfest concert